BMW has been criticised for putting some of its cars features behind a paywall, requiring customers to pay more to access certain features such as heated seats.

It has led to accusations that the company is exploiting its customers, due to the majority of these features being available as standard in many modern vehicles on the market. Also, the status of the paywall can vary through the vehicle’s life and successive owners.

Due to these features already being installed during vehicle production this may prompt drivers to take vehicles elsewhere and pay to have them ‘turned on’; however, this opens the vehicle up to the risk of cyber-attacks.

We spoke to Ant Martin, chief engineer and head of vehicle resilience, Horiba Mira, to learn more about why paywall vehicle features may result in unintended consequences and create cyber fragility.

Just Auto (JA): Could you tell me a little bit about your role and background on the company?

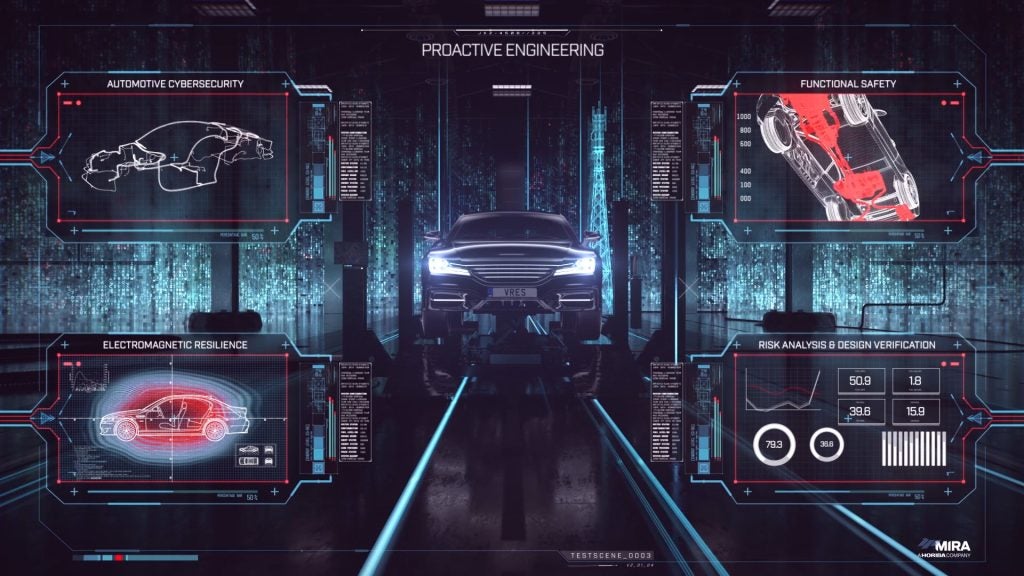

Ant Martin (AM): I’ve been with Horiba Mira for over 20 years. I came through the roots of electromagnetic resilience. In 2018, I became head of vehicle resilience which covers cybersecurity, functional safety, and also electromagnetic resilience – those are the three key pillars.

Essentially, what we’re doing is looking at the threats to the features, functions, and operations within vehicles, and also the infrastructure that they need to operate within.

There are other attribute groups, certainly within Horiba Mira, and within vehicle manufacturers, who look at actually implementing features. It’s their job to ensure that ride and handling is correct, that connection to autonomous features and functions are implemented in the vehicle; then it’s our job to make sure that once those features are implemented correctly, that they are then safe, secure, and robust from that point onwards and throughout the lifetime of the vehicle.

For cybersecurity it’s somewhat different to some of the other vehicle attributes. The latest regulations call for a requirement to monitor vehicles and detect any kind of attacks, understand them, and then respond to them appropriately throughout the full lifetime of the vehicle and until that vehicle is completely off the road.

BMW has been criticised for putting certain features behind a paywall. How could this decision potentially see a rise in cyberattacks?

One of the specific things that we have to do as part of the requirements of regulation 155 for cybersecurity is a TARA, which is a Threat Assessment and Remediation Analysis.

Essentially, what that means is that we have to look at all known scenarios; there are some things that we don’t know, they’re called unknowns. We can try and do as much as possible to try and reduce the unknowns, but what we have to do is go through all of the scenarios, we have to look at all of the things that we want to protect in the vehicle.

Then we have to look at the attack surface on the vehicle and how attackers could get to those things that that we feel are high priority in terms of being protected. Then we have to look at who may be looking to hack a vehicle or attack the vehicle, all the data within that vehicle and why they might want to do it.

We have to go through that process and one of the areas of concern is that we already have a model of owners and tuners who try to extract full performance and full feature sets from vehicles. For example, remapping engine electronic control units (ECUs) has been big business over a long period of time. Some people would say: “It’s my car and I can do what I want with it.” Actually, the Computer Misuse Act says differently, and it’s not legal for owners, or for them to get tuners, to modify the software within ECUs.

Tuners and owners will be motivated by the fact that they may be disgruntled about the value, that they feel they’re forced to buy a vehicle because they have to get from A to B. They then feel disgruntled that features that are on the vehicle itself can be switched on and off and are then hidden behind paywalls.

For those who are motivated enough and capable enough, they are either going to pay somebody or do it themselves to try and release those features so that they feel that they are getting more value. That seems to be the general motivation around that area.

The biggest problem that we see is that whilst they’re in there, they could be doing all manner of things because this is no longer just a feature set within an ECU that is not connected to other ECUs.

Now what we’ve got is some very large computing capabilities within vehicles that cover a huge number of features and functions. Whilst you’re messing around with one feature, you realistically don’t know what you’re doing with the others.

These vehicles go through millions and millions of pounds worth of validation, and it is a very significant process to be able to implement a feature and then, from a vehicle manufacturer’s perspective, feel confident that you’ve done enough to release that feature out onto the road.

When looking at the threat landscape, have you seen any new trends emerging in the cybersecurity space?

We’re certainly seeing that there is a massive increase in terms of the attack surface of the vehicle, that opportunities are increasing massively, as is the complexity of software. Once you start to get into threat actors that have significant capability, and are starting to extract firmware off vehicles and studying firmware to try and find vulnerabilities and weaknesses, then with the complexity of software it means that there are more defects for the attackers to try and leverage.

For instance, with the work that we do within the automotive industry we pride ourselves on the fact that we work on numbers of around one to three defects per 1,000 lines of code for a typical prestige vehicle which has got around about 100 million lines of code. That means that we work on the basis of there will be 100,000 to 300,000 defects in our code.

Those defects could open opportunities for attackers which could cause a security, safety or functionality issue. Therefore, as you increase the amount of code, if your defects rate stays the same, then essentially, you are opening up more opportunities.

The other problem we have to contend with is that software is getting more complex, and therefore it is getting increasingly difficult to keep down to one to three defects per 1,000 lines of code.

As an industry what other challenges are you facing?

Within cybersecurity and especially in automotive cybersecurity there is a massive skill shortage. So therefore, not only from a vehicle manufacturers’ perspective in terms of implementing secure features and having the people and teams around them to do that or within the company, but also for independents like us, having the teams and the number of people that are required in order to cope with the growth of needs – it’s a huge challenge. There realistically needs to be a call-out across education, that this is a massive growing area and something that we should be encouraging young engineers into.

Also, there are not enough women in this in this area; cybersecurity engineering is a great area for everybody to work in and has significant opportunities. Everything in terms of complexity and the threat scenarios are growing which means that this is a growing area, and it’s a good area to get employed into and learn more – huge opportunities.

Alongside this there’s a real need for diversity. From a cybersecurity perspective, we’ve got a lot of algorithms, there’s a lot of science, physics, and everything else, but the one thing that we believe have that the other attributes don’t, is a human element. We have to understand the human thought process the attackers have, we have to put ourselves in the attacker’s shoes to understand what their motivation is, and that’s where we can understand why pay per feature is problematic because there is a motivation.

Also, if you don’t have a diverse team, then how are you going to be able to fully understand the risks and assess those risks and analyse those risks if it’s just one person from one background? It narrows our scope.

When looking at this issue of cybersecurity, what do you see the future holding?

I think there’ll be a lot around financial, not necessarily the pay per feature, but certainly pay at pump and services like that. There’s a lot of information that will be held within the vehicle from a financial perspective, and attackers are trying to gain access to that information.

You’ve got to be open minded. If you’re not in this industry, if you don’t do this kind of work, then your idea of an attacker might be somebody with a hoodie, sat with a laptop, trying to try to get this information.

Equally when we look at this, we have to look at the complete lifecycle of the vehicle; somebody could be human engineered and working in production of the vehicle, and they could be implementing firmware into ECUs because they’re being blackmailed, or they’re being paid.

It’s not necessarily the people that you would think of. You put yourself in the position as an owner of a vehicle, you don’t see yourself as somebody bad in a hoodie. Perhaps when you’re spending £200 to have a feature unlocked in a vehicle, you don’t see the tuner as that type of person, either. There are a lot of threat actors, so I would say significant issues will be around the financial transactions from vehicles.

We also need to understand that attackers within this area are not just going to be looking at the vehicle itself, but also the infrastructure. We have things such as vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-roadside; if you can spoof those kinds of messages, then you can make the vehicle think that things that are there such as green lights on traffic lights are actually different. They are going to be more seriously motivated threat actors who are looking at that type of area.