The global transmissions market has changed rapidly in the recent past. The requirement for greater fuel efficiency in particular has brought a great deal of dynamism to the global transmission market. In this month’s management briefing we bring you selected extracts from just-auto QUBE’s research service, Global light vehicle transmissions and clutches market. This second feature looks at the political and economic background in which the sector operates.

Political

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The two over-riding political or policy drivers, which have determined much of the direction of the automotive industry in recent years, surround safety and the need to reduce fuel consumption and emissions.

Transmissions can contribute here in the terms of fuel consumption and emission rather than safety – and examples of the different fuel efficiency performance of manual and automatic transmissions are discussed below.

In terms of fuel economy, the political drivers are two-fold, ie the need to reduce emissions and harmful greenhouse gases especially, but also energy security. China for example lacks its own major oil supplies so it would not be surprising to see an eventual political driven shift to full electric vehicles in China as the government seeks to reduce its dependence on external supplies of energy.

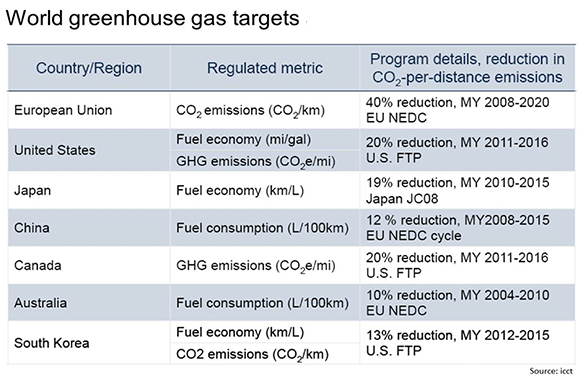

The increasing global focus on fuel economy and CO2 emissions regulations is a key driver of developments in almost all automotive sectors presently and “behind the scenes” it is undoubtedly a key driver of change in transmissions technology.

The significance of CO2 as a political driver can be traced back to the USA in the 1970s in the immediate aftermath of the first OPEC oil price shock. This led directly to the first Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards in 1975. It was also accompanied by a rise in the awareness of the environmental impact of fuel emissions in the US and later the rest of the world, starting in Europe. This is discussed more fully in the Regulatory section below.

Since 1975, US CAFE standards have been progressively updated, and made tougher and more demanding.

The CAFE level was 27.5mpg for cars and 21.6mpg for light trucks in the 1980s. Vehicle manufacturers failing to comply were fined US$5.50 for every 0.1mpg that the fleet exceeded the standard multiplied by the number of vehicles sold in the year concerned. Car companies selling less than 60,000 vehicles per year in the US were exempt from complying with CAFE regulations. Numerous changes have occurred since then and these are detailed below.

In addition, a key political influence has been the California Air Resources Board (CARB). The Californian Air Resources Board (CARB) 2009 ZEV (zero emission vehicles) Regulation states that without credits emanating from ZEV, enhanced AT PZEV, AT PZEV or PZEV vehicles sold in the state, vehicle manufacturers will be penalised US$5,000 for each ZEV credit vehicle not sold. This is forcing vehicle companies to introduce ZEV vehicles of one form or another, full electric or plug-in hybrid.

The European Union adopted similar regulations in 2009 after it became clear that attempts by the OEMs to self-regulate to 140g/km by 2012 were failing. The EC demanded that by 2012 the average CO2 emissions of a vehicle manufacturers’ annual new car fleet must be 120g/km, as measured by the NEDC cycle. However, vehicle manufacturers were given some leeway with a 2012-15 phase-in period as discussed below. In addition, the European Commission has planned for further, i.e.in June 2013 a target of 95g/km was agreed for 2020.

Economic

The key economic issue concerns fuel consumption – and debate continues as to whether manual transmissions are more efficient than automatics.

It is only in recent years that the key economic driver, fuel costs, has come to the fore in North America. Although the US did respond to the 1970s Oil Crisis with the first CAFE rules (see above and in more detail below), fuel costs did not rise to anything like the same level as in Europe. Here the issue of fuel costs became a region-wide issue of concern in the 1970s and undoubtedly stalled any moves to larger engines which may have been nascent at the time; moreover, the improved efficiency of manual transmissions compared to the automatics available at the time helped to limit the growth of automatic transmission use outside the large car segments.

Since the 1973 Oil Crisis, European pump prices have risen continuously and especially so in the recent past; moreover, any occasional negative trends in crude oil prices have not generally been reflected in a corresponding downwards adjustment in the price of fuel paid at the pump. In Europe, consumers – especially those in the UK – now appear to have become inured to rising fuel prices. To some extent, European consumers have compensated for higher fuel prices by buying smaller cars than their North American counterparts buy. And recognising the preference for small and/or compact cars in Europe, the premium brands, who have historically tended to produce larger, more fuel inefficient vehicles, with automatic transmissions, have moved down into the compact and small car segments in recent years. Small cars like the Audi A1/A3, BMW 1-series and Mercedes A-class are now commonplace: but little more than a decade ago, small cars from premium brands were very much the exception to the rule.

Rising fuel prices are one of the reasons behind the trend to smaller cars, with the other most significant trend being the rising traffic congestion in the world’s major cities: finding a place to park has become more and more of a challenge in many cities, rendering smaller cars attractive to premium brand consumers used to large cars. Premium brand drivers are also typically used to automatic transmissions, and to some extent the move of premium brands into the small and compact segments has boosted demand for automatic transmissions in Europe: an A3 is easier to park than an A4 for example.

In the larger vehicle segments where automatic transmissions predominate, and are sometimes the only transmission available, any fuel economy penalty due to their relative inefficiency compared to a manual versions is believed to be “bearable” on the part of consumers in this segment. They have traditionally always had – and in many cases still have – sufficient disposable income to afford the additional fuel costs which these vehicles incur.

Fuel efficiency is of increasing concern across automotive markets around the world, including in North America, where low fuel prices by world standards have been consigned to history.

The issues of fuel prices and consumption are regularly covered in the industry press and web media. For example, the respected US website www.edmunds.com did just this in September 2013, noting how:

- The 2014 Chevrolet Cruze achieves 33mpg on the manual version (28mpg on the urban cycle and 42mpg on the highway). However, when fitted with an automatic, the car is slightly less fuel-efficient, at 31mpg on the combined cycle. Edmunds notes that even this should result in a saving of around US$100 pa in fuel costs for a typical driver.

- By contrast, the 2014 Ford Focus does better with the automatic version; here the six-speed automatic returns a combined cycle of 31mpg, 1mpg better than the manual version.

- Meanwhile on the 2014 Nissan Versa, the manual and automatic versions both achieve 30mpg on the combined cycle – but the CVT version achieves 35mpg; Edmunds also notes that the 2013 BMW 328i sedan achieves 26mpg in both manual and automatic versions.

Fuel emissions also have a direct impact on consumers, especially in countries such as the UK and France where vehicle taxation in linked to CO2 emissions. The French bonus/malus scheme is provides a good example of the impact on consumer behaviour.

The bonus/malus scheme was introduced by the French government in 2008 and since then the generosity of the bonuses has been eroded while the range that maluses is applied to has been broadened. This approach to vehicle taxation has had a profound effect on the make up of the French market. By 2010, vehicles emitting less than 120g of CO2 contributed 47% of the market, from 18% in 2006, while the market for vehicles over 160g CO2 has mostly disappeared. The scheme has also had the desired effect on total CO2 emissions of cars sold. Emissions hit the 130g mark in 2010 against 149g in 2008 when the scheme was introduced.

Taxation policies have driven technological change into the vehicle manufacturers due to the need to remain competitive in CO2 emissions. Among these changes has been an increase in the efficiency of transmissions of all types and accompanying changes in transmission demand patterns, often driven by the relative CO2 emissions performance.

With the gap between a manual transmission’s efficiency and that of an automatic narrowing, it’s legitimate to ask whether automatics will eventually prevail in all markets.

Depending on driving style and prevailing road and traffic conditions, traditionally drivers have been able to achieve anything up to 10-15% fuel efficiency saving in a manual transmission compared with an automatic. As automatic transmissions have improved in terms of fuel efficiency, i.e. economic terms, vis-à-vis manuals, the question can be asked as to whether automatics will one day replace manuals entirely, especially in view of their general accepted convenience for drivers.

The forecasts in QUBE suggest that manuals will remain the most significant transmission type in the long run, largely because of the degrees of mass motorisation (which tend to start with manuals) which have not yet taken place in India, China, Russia and other new markets. We project that even in the late 2020s, close to 60% of the global market will have a conventional manual transmission.

The rest of the market will divide between conventional automatics, dual clutch systems (DCTs), continuously variable systems (CVTs) and indeed electric vehicles. In general, we expect the US to remain with automatics because of the embedded manufacturing systems at the VMs there – and conversely in Europe where most of the VMs have their own manual transmissions factories which supply the majority of the cars built in Europe, the trend away from using these facilities will be slow.

From the VMs’ side, the economics of transmissions development can be very efficient in terms of reducing emissions and fuel consumption, especially relative to engine development costs.

While the scope of fuel economy improvements emanating from improved transmissions is narrower than that available to engine design improvements, it is generally accepted that improvements to transmissions cost less than engine developments. Typically, according to ZF, the driveline contributes about 15% of the energy losses in a vehicle, compared with nearly 50% for the internal combustion engine. However, reducing losses derived from the engine are typically much more expensive than addressing transmission development. For the OEM, it’s far more cost effective to add gears to a transmission, alter the ratio spread, change the transmission oil pump, introduce lock-up torque converters etc. than it is to introduce radical engine technology such as variable compression ratio or HCCI engines.

For example, the cost of five-speed manual transmission is typically between GBP400 and GBP500, to upgrade to a six-speed brings an on-cost of 10-20% in return for a fuel economy improvement of around 4%. Engine technologies, while having a greater scope for CO2 reduction, typically cost an OEM far more to implement and thanks to tightening exhaust gas regulations – particularly around the cost of after treatment for NOx and PM – the cost of engine technology continues to increase. The cost-benefit equation has been a major driver behind the near ubiquity of stop-start system installation on transmissions – stop-start can benefit CO2 by anywhere between 4 and 8% in exchange for an on-cost of less than GBP200.

In the future, more cost will be introduced to automatic transmissions as they become increasingly adopted for hybridisation. While the fuel economy benefits of hybridisation is not denied – ZF’s full hybrid version of its 8HP transmission improves fuel economy by 21.1% compared to its 8-speed with stop-start – hybridisation of the transmission comes at a significant cost. The ZF unit integrates the hybrid electric motor, together with a clutch to disconnect electric drive, into the same packaging space as the non-hybrid 8HP. The real increased cost of the unit comes from the use of rare earths in the electric motor which can effectively more than double the cost of the fully hybridised transmission.

See also: October 2013 management briefing: developments in transmissions (overview)

|