Europe-wide 'eco-labelling' is already influencing the way consumers view white goods at the point of sale. It is now coming to passenger vehicles and could have very significant implications for transmission design, writes Tony Lewin.

More than eighty percent of European consumers shopping for refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers and other household appliances base their choices on the eco label attached to the product and displayed in all advertising and point-of-sale material. The multi-coloured arrows on these labels depict the range of efficiency classes from A (green) to G (red), with the individual product's rating highlighted with a larger arrow of the appropriate colour. For Europeans it has become second nature to shop for the green A label – so much so, in fact, that in the case of refrigerators there was such a migration to A-grade products that the authorities were forced to introduce an A-plus grade to allow buyers do distinguish the very good from the merely good.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Now the eco labelling scheme is to be introduced for cars so that consumers can see at a glance which models have higher or lower CO2 emissions. Though final details have not yet been decided, the new labels will have to be displayed in advertising as well as on the windshield in the showrooms. Right now, the many hundreds of vehicles on the European market span a CO2 emissions spectrum with almost every value from 87 g/km to well over 300 g/km. Splitting this continuous spectrum up into separate bands – for instance under 100 g/km, 100 to 120 g/km, 120 to 150 g/km and so on – divides up the models by colour band so consumers can readily identify them.

So, what does all this have to do with transmission design?

In countries such as the UK where the eco-label has been trialled in showrooms, there is anecdotal evidence that consumers do find it easier to differentiate at a glance between different CO2 emissions values and that, just as with fridges and washing machines, they are drawn to the more efficient products as a result. In a market becoming increasingly focused on energy saving and emissions reduction, automakers — just like white goods producers — want their products to appear as efficient as possible.

A side-effect of any banding scheme is that consumers tend to look at which band a product falls into, rather than looking for the detail of its absolute CO2 emissions value. Thus a model close to the top of a hypothetical band C, at say 148 g/km, might appear economical and efficient. Yet it is actually much closer in emissions to a car that's just in the higher-emission band D, at 151 g/km, than an apparently comparable competitor in the same C band but which is right at the bottom, at say 121 g/gm.

For this reason, says Ralf Najork, group vice president of R&D at Getrag, automakers will make every effort to tweak their vehicle specifications to nudge particular models down a gramme or two if they are close to the cut-off point between one colour and the next. That way, the perceived advantage to the consumer will be great, even if the actual improvement is less impressive.

"This means the ability to vary gear rations with each existing transmission design will be important, and that the flexibility to accommodate late changes will become a requirement."

A model could easily drop from band D (150 – 185g CO2) to band C (121 – 150g) simply by fine-tuning one or two of its internal gear ratios, he said. In many cases this could be simpler than making other adjustments.

Automatic concern – and DCT opportunity

Where the colour ratings will impact particularly heavily on customer perceptions is when it comes to automatic transmission options, observes Najork. Citing the case of medium-sized vehicle with a 5-cylinder diesel engine and manual six-speed transmission, he noted that while the manual model had CO2 emissions of 178g/km, the version with a six-speed automatic has its emissions boosted to 203g/km. This pushed it up two whole colour bands, creating a formidable consumption step for the buyer to have to accept. In a second example of a two-litre gasoline turbo vehicle, going from six-speed manual to an automatic with the same number of ratios raised CO2 by 14 g/km, resulting in a single-step increase in its colour banding.

|

Conversely, while many planetary automatics are shown up in a poor light by the system, colour banding could be a powerful opportunity for automatics based on dual clutch technology to demonstrate their superior efficiency. Najork contrasts the turbo gasoline model cited above with another example – an all wheel drive turbo gasoline model in the same class. With a six-speed manual transmission this model emits 172g/km CO2; with the optional seven-speed dual clutch transmission the emission figure is just the same.

Najork does not say which model this is: however, only Audi models combine the parameters he mentions, and the DCT in question is a second-generation unit — Audi's latest seven-speed. Yet even first-generation DCTs can show up favourably in the colour banding scheme: the Ford Focus 2.0 diesel emits 153 g/km with a six-speed manual and only slightly more – 159 g/km — with its wet-clutch six-speed DCT, thus keeping it in the same CO2 colour band.

The gap is narrower still with the very latest dual dry clutch transmissions, in particular Volkswagen's seven speed DSG, as in the latest Golfs and Polos. A Golf 1.6 TDi with manual transmission gives 119 g/km, while with the dual clutch the figure is 123; in the super-economy BlueMotion Golf line the gap is further narrowed, with the manual scoring 107 g/km and the DSG 109.

As launch customer for the latest second generation dry-clutch DCTs from Getrag, Renault is aiming at CO2 neutrality for its automatics — that is to say no emission difference as a result of opting for the automatic version

|

Extending the example

Taking the above example of the five-cylinder diesel car – actually a Volvo V70 station wagon – Najork computed the likely emissions value of the same vehicle if it were fitted with a seven-speed DCT in place of the manual transmission. Najork's figures reveal a fall in CO2 emissions compared with the manual, thanks to the superior efficiency and programming of the DCT – enough to drop it into the next-lower CO2 emissions colour band. The value in advertising and on the showroom floor of such clear evidence of improved fuel economy and lower CO2 taxation liability would be substantial.

Extrapolating this thinking still further, Najork maps out a scenario where the base car – in this case the 2.0 litre Ford Focus diesel – is graded band C for CO2 emissions. With a planetary automatic its CO2 would rise 15 percent and the model would be demoted to band D. The current DCT version, just 4 percent heavier on CO2 than the base car, stays within band C.

|

Adding Getrag's Assisted Direct Start stop-start system to the current DCT car would bring its economy back above that of the base car and gain a band B colour rating; switching to the second generation six-speed DCT with ADS would result in a further 7 percent improvement, though still staying within the B banding. Finally, says Najork, the seven-speed version of the new dry-clutch DCT, in conjunction with ADS, would be enough to clinch a 12 percent reduction in CO2 output and a move into the best A band on the eco label.

Once more, the value of the colour bands as a selling tool can be clearly seen, and it would be relatively straightforward for carmakers to fine-tune gear ratios, manipulate transmission options and strategically provide extra features such as stop-start in order to promote their models into better CO2 colour bandings.

Added focus

Recognizing that some automakers might relax too much once their vehicles were safely in the better CO2 bands, the European authorities plan to further tighten the ratings from 2013. What is now a band A will become band C, while band C will become band E. This will open up new colour bands below the 100 g/km mark and, it is hoped, stimulate competition among manufacturers to populate the new classes with vehicles that are even more efficient.

The result is that there is likely to be an even greater consumer focus on fuel efficiency and CO2 bandings.

Once again, the opportunities for automakers are clear. Designers could strategically tailor the size of hybrid assist packages, or even the size of battery packs, to meet specific CO2 band targets, and the amount of electric boost provided during the drive cycle could be fine-tuned for similar results. Getrag estimates that its mild hybrid Powershift transmissions, with an e-motor of just 15 kW, can trim CO2 output by 15 to 20 percent, enough to promote the vehicle by a full two colour bands on the eco-label. In this way, maximum apparent efficiency benefit could be obtained for an optimum cost and engineering outlay.

|

Flexibility

Even though the regulatory and fiscal environment surrounding vehicle fuel consumption is becoming tougher and more complex, it is clear that automakers now have many more tools at their disposal with which to reduce and fine-tune the CO2 emissions of their models. Flexibility for late changes in gear ratios is just one example of how a carmaker could boost the eco rating for its product: the minimal engineering outlay involved would be small in comparison with the substantial commercial boost obtained by the model moving up to a more advantageous colour band.

Efficient DCTs, especially when combined with mild hybrid technologies harvesting braking energy, have the capacity to promote a vehicle one or two categories higher in the CO2 efficiency bandings, again providing significant commercial advantage.

Much work remains to be done on the implementation of colour banding; not least among the challenges is to get agreement on the CO2 values denoting the bands, as well as deciding whether the bands should depict absolute values or performances relative to other vehicles in the same class, as is the case with the Euro NCAP safety ratings. One way or another, however, the introduction of CO2 labelling on the European market is likely to have a major influence not just on consumer behaviour, but also on how automakers design, develop and fine-tune their model specifications.

——————————————

Working out the numbers

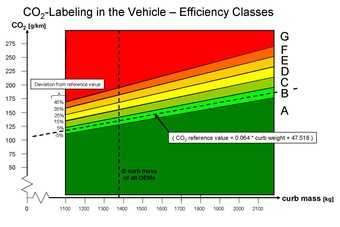

The calculations underpinning the scheme may turn out to be more complicated than the simple mathematics behind the white goods ratings. It has yet to be decided whether the colour band of a model will represent its absolute CO2 emissions level, or whether the colour should indicate its relative CO2 output compared with other vehicles of similar size and role.

Most European organizations favour the representation of absolute CO2 values, as this is clearer to the consumer and enables vehicles to be compared across different market segments. However, in 2007 the EU decided on a different formula when it needed to work out how to compute corporate average CO2 ratings for the Union's upcoming CAFÉ regime of targets, penalties and bonuses.

The CAFÉ scheme is based on vehicle weight, meaning that the heavier the vehicle, the more CO2 it is allowed to emit before it gets penalized. In the unlikely event of this being adopted for the eco-label scheme, it could affect the colour banding in counter-intuitive ways. The mean curb mass of European vehicles is around 1375 kg: a car with this mass emitting, say, 125 grams per kilometre CO2 might be banded B, or pale green. Yet a lighter car, of say 1100 kg, and still emitting 125 g/km CO2, would be pushed into a higher band, perhaps borderline C-D – as if it represented a higher emitting product – which it clearly is not. More paradoxically still, were a much heavier car of perhaps 1800 kg also to achieve 125 g/km, it would be rated grade A dark green, or the best for efficiency.

|

Although such CAFÉ rules appear to unfairly penalize light cars, which will clearly be more economical overall and thus emit fewer grams of CO2 for every kilometre travelled, it must be remembered that this type of colour label would be a rating for relative efficiency, not for absolute emissions values. A parallel with refrigerators could be useful here. Both a compact undercounter fridge for a small apartment and a large, twin-door fridge for a large family home might be rated grade A green for efficiency, but the bigger fridge will clearly consume more electricity.

The Brussels-based Federation Internationale de l'Automobile explains the dilemma clearly on its website:

FIA European Bureau Technical Director Wilfried Klanner, however, points out that relative labelling could mean small cars with low CO2 emissions being labelled "D". Large cars with higher CO2 emissions could be labelled "A", if they were the best performing in their category.??"I'm confident that an absolute label will come about," explains Klanner. "Most proposals seem to be going in a similar direction. The majority of clubs are in favour of an absolute label independent of the vehicle size. We need pressure to downsize cars and encourage consumers to buy cars with lower CO2 emissions," he adds.

This article first appeared on DCTfacts.com