Tinius Olsen Helps Drive Automotive Sustainability Through Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technology

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak recently announced that ‘a new electric vehicle is being registered in the UK every 60 seconds’ as he outlined the government’s decision to delay the ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles until 2035. That’s just under half a million cars a year at the present rate but the question is already being asked, which power source to the electric motor is going to be the best option in the drive to net-zero, battery or hydrogen fuel cells?

Let’s consider the pros and cons between battery and fuel cell powered vehicles. Well, both are extremely environmentally friendly, cheaper to run than the fossil fuel variety, require less maintenance, and some of them are extremely quick.

On the downside there’s limited battery range, battery lifespan issues and cost, long charging times and, ironically, environmental impact implications based on current non-sustainable electricity generation for charging and the processes and materials involved with battery production.

So, all things considered, the electric battery option seems to have one or two issue’s to overcome, a situation further compounded by the process of adding hydrogen to your car being just like your normal weekly fill up at the gas station- what’s not to like? Let’s delve in a little closer.

“Firstly, neither of these technologies are new,” says Loughborough Principal Research Engineer at Intelligent Energy Oliver Jackson, who are the UK’s leading manufacturer of hydrogen fuel cells.

‘What we recognise as the first hydrogen fuel cell was invented by Welshman William Grove in 1838, with the modern electric battery invented by Alessandro Volta some forty-two years earlier. Both technologies were vying for the upper hand in terms of vehicular power-plants until the internal combustion engine proved more convenient to use and the die was cast for the next 140 years or so” continues Oliver.

Fuel cells themselves work like batteries, but they do not run down or need recharging and they produce electricity as long as hydrogen is supplied. They consist of two electrodes, a negative electrode (or anode) and a positive electrode (or cathode), sandwiched around an electrolyte.

A fuel, such as hydrogen, is fed to the anode and ambient air is fed to the cathode. In a hydrogen fuel cell, a catalyst at the anode separates hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons, which take different paths to the cathode. The electrons go through an external circuit, creating a flow of electricity, whereas the protons migrate through the electrolyte to the cathode. A catalyst at the cathode combines the protons with oxygen and the electrons to produce water vapour and heat.

“It’s an intrinsically simple system but highly efficient and of course extremely green at the tailpipe, producing only water vapour, so to speak, and doesn’t rely on electricity from the National Grid,” continues Oliver

“The technology can be applied across a broad range of uses too, such as the aerospace industry, with the eventual aim of replacing fossil fuel powered jet engines with electrically powered alternatives now becoming increasingly realistic. It’s really, really exciting stuff.”

Intelligent Energy emerged as a spinout from Loughborough University in 2001, where the first fuel cell project began in 1988. Twenty-two years later, following collaborations with the likes of Suzuki, Airbus, Boeing, and latterly BMW, the company now employs 250 people and has partners and customers around the globe.

“The technology has come a long way in the last 35 years or so. Our collaborations with major global companies have been a big contributor to this and these market forces are continuing to drive things forward. The need to reach net-zero is obviously the main consideration, as well as reducing the cost but to achieve this, we will need to produce lighter, cheaper and even more efficient fuel cells to help reach these targets- this is now our biggest challenge.”

“This puts materials testing at the forefront of R&D, because if lighter or cheaper materials are found to work just as well, after rigorous and extensive testing, then that saving can be built into the bottom line, creating a more cost effective, viable option.

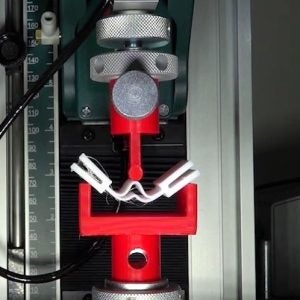

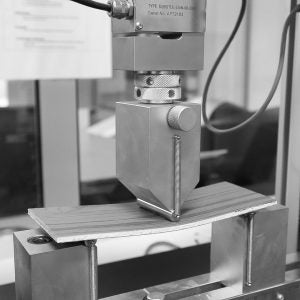

“Our own in-house research team are using the Tinius Olsen equipment to test materials for mechanical properties; tensile, compressive and bending strength, stiffness etc. For example, when we are developing lightweight systems for aero and UAV applications, we test thinner and lower density materials to make sure they are strong and durable enough for their intended purpose.”

“The testing lab is also used to test other areas such as electrical resistance and testing of coatings. Another key area is the transport properties of materials such as the carbon papers we use for our gas diffusion.

“For all these properties, we need to apply a range of forces to see how they will respond to changes in pressure.”

“There are also things like gaskets and seals, we do quite a lot of testing on those, as well as supporting other departments across the business such as the mechanical design team, where they need to test new designs and prototypes. Material properties data is used by our modelling teams and quality and production teams for things like testing batch variability of products and defect analysis.”

“All in all, the Tinius Olsen equipment and support we receive is fundamental to what we do, so you could say they’re very much on the front line of these developments, generating confidence in materials used and the finished product.”

Intelligent Energy has not been distracted by changes to net-zero deadlines and is continuing its development of hydrogen fuel cell technology at a rapid pace. With major automotive manufacturers such as BMW and Toyota actively producing their own hydrogen powered cars, IE’s work could well see this technology competing with, if not replacing, the current battery powered options.

It’s definitely full steam ahead, Rishi Sunak’s 2035 announcement or not.